Are you up-to-date? Penn State Health colorectal screening survey gains national attention

By Carolyn Kimmel

Life could look a lot different for Mike Hamonko than it does, thanks to a screening colonoscopy that many people turning 50—the recommended age for average-risk screening—dread and often postpone.

Lucky for him, the Harrisburg-area resident didn’t attach any particular aversion to the procedure—or the colon-cleansing process the night before—so he scheduled it right away.

“The prep was annoying, but annoying isn’t that bad, considering they can catch something as bad as cancer,” said Hamonko, whose primary care physician recommended the screening test.

He awoke from the procedure to the surprising news that he had a precancerous tumor.

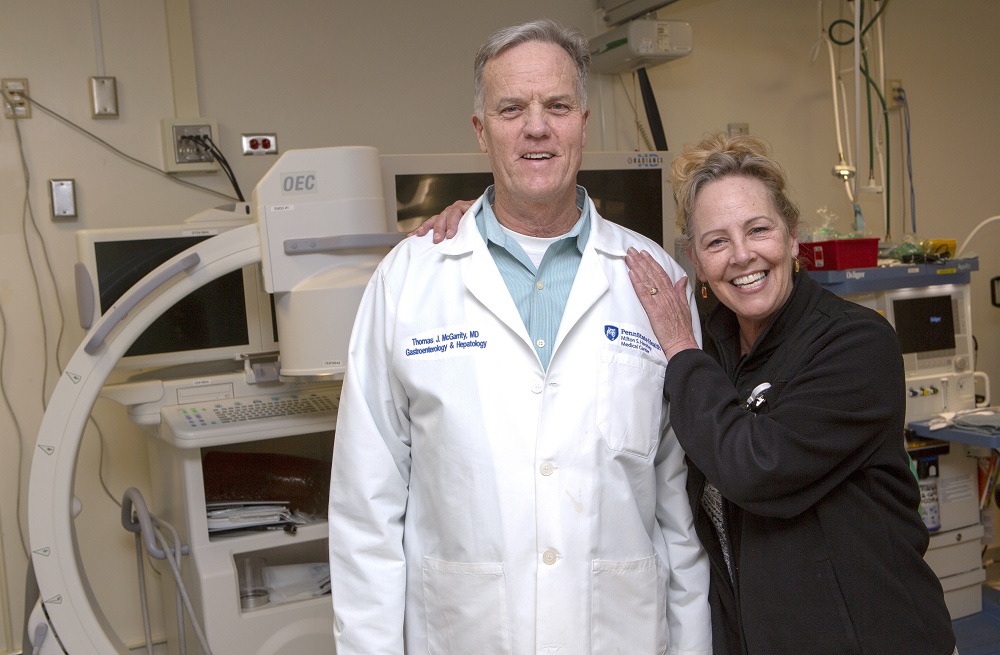

“Mike’s case shows the importance of the family doctor making the screening recommendation and the patient following up,” said Dr. Thomas McGarrity, gastroenterologist at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. “Mike had no symptoms and no family history of colon cancer.”

Screening is important because it can find precancerous polyps—abnormal growths in the colon or rectum—so they can be removed, and it can find colorectal cancer at an early stage, when treatment often leads to a cure.

“This is really the only cancer where we screen to find and eliminate pre-cancer. Most other screenings are looking for early cancer,” said McGarrity, who is on a crusade to get primary care doctors to recommend screening.

Of all cancers that affect both men and women, colorectal cancer is the second-leading cancer killer in the United States. Many people know they should get screened but don’t. One reason why is lack of effective reminders from their doctors, coupled with patient fear and lack of insurance coverage, McGarrity said.

Spurred to action by a Community Preventive Services Task Force recommendation to increase colorectal cancer screening and a National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable (NCCR) Initiative that challenges an 80 percent compliance to screening guidelines by 2018, McGarrity decided to start in his own backyard—with his fellow employees at Penn State Health.

He developed a first-of-its-kind colorectal cancer screening program that was launched in the fall of 2017 to survey Penn State Health and Penn State College of Medicine employees about whether they were up-to-date on colorectal cancer screening.

The voluntary, anonymous survey was sent to all employees over age 40 by Penn State Health’s Human Resources Department. The survey asked about screening compliance and family history of colorectal and related cancers.

The health system’s report card returned high marks. For employees at average risk, 81.2 percent had been screened, a statistic that put Penn State Health above the goal set by the Roundtable Initiative.

The NCCR’s “80 percent by 2018” initiative involved more than 1,500 organizations—including medical professional societies, academic centers, survivor groups, government agencies, cancer coalitions, cancer centers and health plans—committing to the goal of 80 percent of adults aged 50 and older being regularly screened for colorectal cancer by 2018.

Results of the initiative won’t be available until 2020, but the NCCR says screening rates are on the rise, and it has continued its 80 percent goal into the coming years. Screening 80 percent of people age 50 and older would result in a 20 percent decrease in cases of colorectal cancer and a 33 percent decrease in deaths.

McGarrity’s screening program has become a national model. The NCCR asked McGarrity to present it at its national meeting, and McGarrity has offered to help other organizations across the country that would like to implement it.

The program is also a model for how to use an organization’s human resources department as an advocate and champion of the cause. “Human Resources protects and promotes health, so I thought it was the natural place to go with my idea for the survey,” McGarrity said.

Despite the outstanding report card that Penn State Health received, McGarrity was startled to find that high-risk employees were not being screened. Twenty-five percent of employees ages 40 to 49 identified themselves as being high risk for colorectal cancer, but only 45.8 percent of them were up-to-date on their screening, he said.

“We surpassed our 80 percent goal for employees at average risk, but there’s obviously more to be done,” McGarrity said. “We’re discovering more and more about genetics, so thinking about family history is especially important.”

He’s currently trying to introduce the survey into Penn State Health family care practices and get the word out to employees at high risk that they should get screened.

But, as Hamonko knows, even those without a family history should heed the screening guidelines.

“That screening may well have saved my life,” said Hamonko, who underwent robotic surgery to remove the precancerous tumor last fall and is doing fine now. “Don’t put it off.”

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email the Penn State College of Medicine web department.