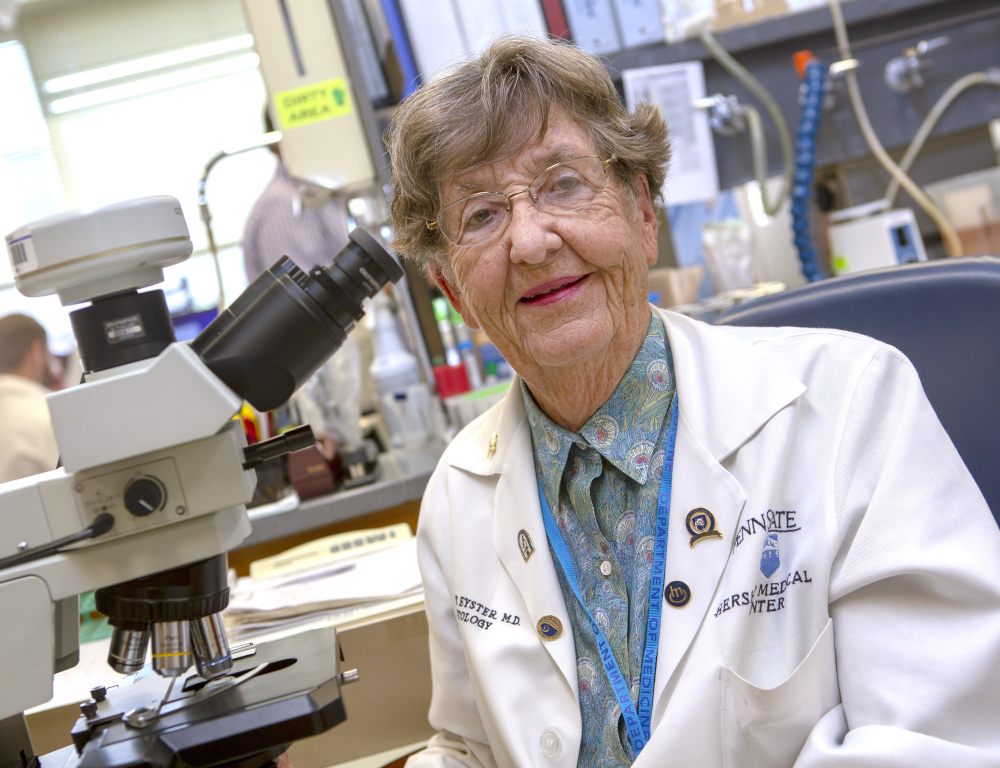

Physician of the Year honor caps off 40-year career of serving hemophilia patients

When Elaine Eyster traveled to Dallas in mid-August 2014 to receive the National Hemophilia Foundation’s 2015 Physician of the Year award, she was more impressed by those in attendance than the plaque she received.

Many there had survived the HIV epidemic. Others had been cured of their Hepatitis C infections.

“Earlier in my career most would have been in wheelchairs or walking around on crutches,” she said. “Because of the availability of good treatment, they are leading active, productive lives.”

When Eyster was in medical school, half of the boys born with a severe form of hemophilia died before their 19th birthday. Those who survived were destined to spend most of their lives on crutches or in wheelchairs as a result of joint and muscle damage from repeated bleeding episodes.

Eyster has spent more than four decades conducting research, caring for patients, working on teams, mentoring others and providing leadership to bring such changes about. That is why the executive committee of the Mid Atlantic Region III Federally funded Hemophilia Treatment Centers and the Hemophilia Center of Central PA in Hershey nominated her for the award.

James Ballard, professor of humanities, medicine and pathology at Penn State College of Medicine, was hired by Eyster 40 years ago as the institution’s second hematology fellow.

“She was my mentor, and we have had a long period of collaboration,” he said. “She is an incredibly talented person who has great scientific skills and is a great problem solver.”

He has seen Eyster care for hundreds of patients with hemophilia and advocate for their well-being on a regional and national level.

“She has been a friend and doctor to many, and I think she has reached a point in her career where it is obvious to everyone that she has made significant contributions scientifically and in terms of patient care and advocacy.”

Eyster’s early research focused on the HIV epidemic in the hemophilia population. In 1982, when three people with hemophilia who had been heavily transfused with blood clotting factors developed an immune disorder similar to those described in gay men, her team was in a unique position to investigate this mysterious illness.

She had saved samples of plasma because she was interested in the transmission of hepatitis by clotting factors.

“At that time, we didn’t know anything about what caused AIDS or how it was transmitted,” she said. Those samples played a key role in helping to explain how HIV infections were transmitted and how the immune deficiency progressed after an individual became infected.

Similar research conducted later with her collaborators at the NIH addressed the transmission and the outcomes of the hepatitis C virus infections that were acquired by almost all people with hemophilia who had received clotting factor concentrates during the 1970s and 80s, before effective donor screening and viral inactivation methods were developed.

“Hepatitis B was a big problem for people with hemophilia, so I was saving the samples because I thought there would be more to learn and I wanted to be prepared by having materials to study it,” she said. “Or – as my late husband would say – because I never threw anything away.”

Eyster was also instrumental in getting state funding to establish The Hemophilia Center of Central PA, which has grown over the years to serve about 450 active patients who now receive comprehensive hemophilia care at Penn State Health.

She hopes the future will bring development of replacement blood clotting factors that remain active for weeks rather than days for people with hemophilia– and that can be given subcutaneously rather than intravenously to prevent and treat bleeding.

Eyster also would like to see researchers find a way to prevent the body from attacking and destroying the transfused clotting factors – or develop an effective gene therapy that will allow people with hemophilia to produce their own clotting factors.

Although she no longer works full time, Eyster gets excited when she talks about the staff at the hemophilia center.

“It’s so gratifying to have such a great team of people to work with and to see what we can accomplish,” she said. “It has been a most rewarding experience to get to know so many families and to help care for so many wonderful people.”

If you're having trouble accessing this content, or would like it in another format, please email the Penn State College of Medicine web department.